"...taking the decision to raise local rice production was necessary and a beneficial one today, because how could we have survived/survive in a time of escalating supply chain disruption and rice price...But raising supply alone and pursuing such expecting normalisation of rice price and availability without remedying other influencing factors is like pouring water down a basket expecting it to fill."

Over the weekend I listened to someone rant about how costly food is with the amount a bag of rice is today.

I understand this concern because rice is a staple and a readily accessible energy source, so when it’s costly then there’s a problem.

But this lament gets me thinking how we take parochial solutions to agricultural issues and don’t think outside the box.

The thinking at the helm of affairs is that if rice is costly to go round, then we must produce more.

For reason that, a surplus is expected will force down price. But this economic function takes not into consideration other influencing variables.

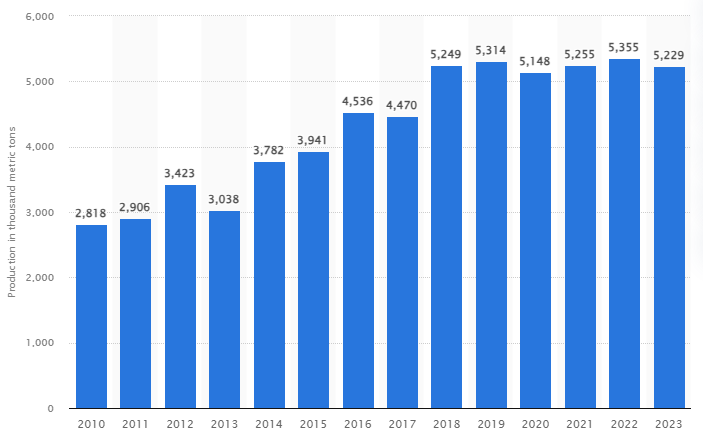

Nigeria’s paddy rice volume grew by 18% from 7.1 million metric tonnes to reach 8.4 million metric tonnes in 2022 from 2015 since the reforms of the previous administration.

And despite this, rice price climbed by 230% from ₦10,000 to ₦31,000 within the same period (or by over 500% today).

What we produce satisfies 81% of our 6.4 million metric tonnes rice demand.

It then means that just 61% of our 8.5 million metric tonnes paddy rice gets to the table.

This is low compared to over 67% expected global conversion standards, one realised by some leading rice producing countries.

Our rice production is still mostly done by small scale farmers who employ/and with manual labour and simple implements, where bulk of grains get damaged to crude/poor harvesting, storage, handling, & processing.

20-40% of our rice is wasted over harvest.

Our mechanisation level is suboptimal, and for these 28 million farmers we have just 7,000 functional tractors for coupling implements like harvester let alone processing & storage equipment.

Even, our paddy rice output had declined from a 10.8 million tonnes peak in 2017 and with a lower 48% derived milled rice.

While quantity appears to have improved even when it decreased, milled quality worsened but was higher in 2018 than in 2017 and this is to other driver factors aside post harvest loss.

Rice production increase realised has been largely by expanding acreage, with cultivated area increasing to 5.9 million hectares (ha) in 2018 from 3.1 million ha in 2015.

This is typical of the crops we lead their production -yam, cassava, cowpea, etc.

But the yield/ha for rice averaged 2 tonnes which is 2 to 3 times lower to what is found elsewhere. Also, cultivated area fell to 5.3 million ha in 2020. Thus, the low yield resulted from poor productivity and reduced acreage.

For low yield/ha the lack of or inadequate use of hybrid seeds, fertiliser, herbicide and pesticide to combat the complexity of infertility, climate change, weeds and pests problems disrupting the normal growth of the rice crop are responsible.

The pest Quela bird invaded rice farms last year decimating over 75,000 ha. Rice blast disease capable of a 100% damage resurged in 2019 (dormant since 2014) to wreak havoc same year the nation’s paddy output dropped drastically.

Since the 1950s several rice varieties that are high yielding, disease resistant, nutrient efficient and environment/climate adaptive have been released and yet farmers still suffer of these.

Complaints by farmers from losses to the above do portray their lack of awareness on and an absence of economic power to adopt the production enhancing inputs and good agronomic practices, which portray the inadequacy of extension and the costly nature of agricultural inputs.

This is unsurprising with the low number of extension agents, one having to serve about 10,000 farmers and the risen prices of diesel, gasoline and fertiliser that have significantly impacted cost of running farm machineries where irrigation and procurement of agricultural input have become a problem.

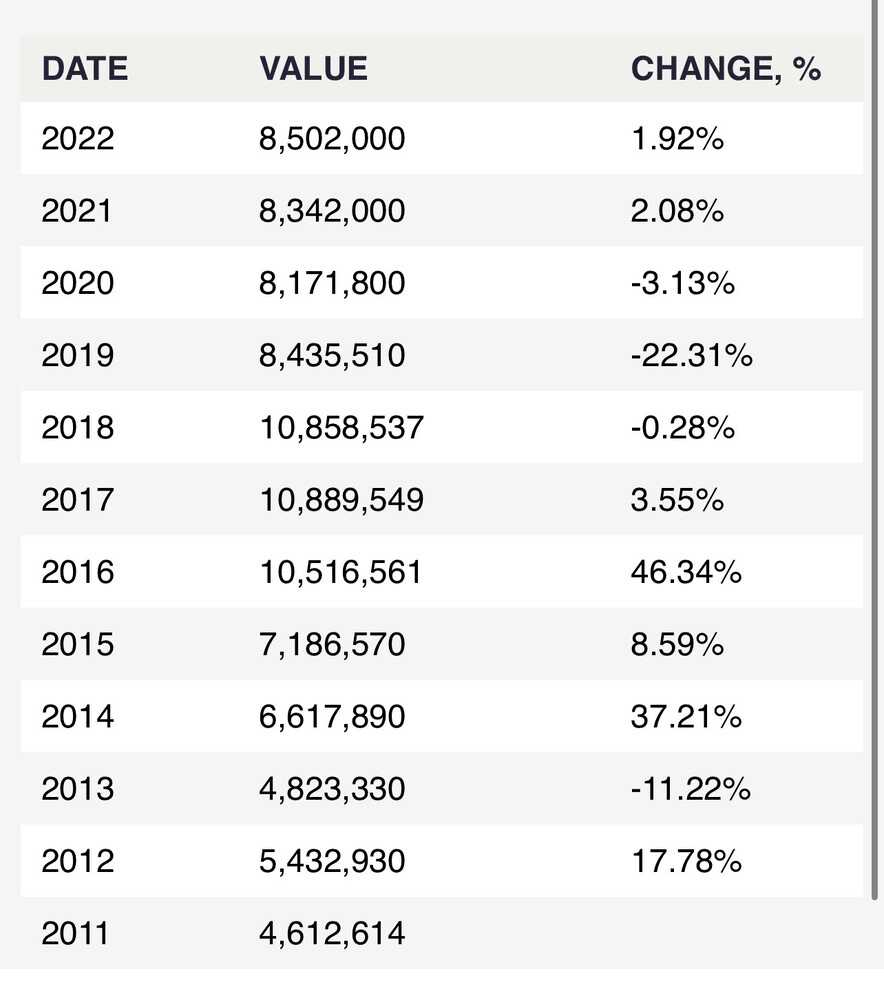

Rice is a fertiliser-intensive crop, and while we have fertiliser plants and with improved output (3 million metric tonnes), the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war disruption of global agricultural input supply chain have affected fertiliser price and supply in Nigeria.

In spite the significant ($121 million) investment in fertiliser increasing fertiliser plants (over 45) and volume through the Presidential Fertiliser Initiative (PFI), fertiliser price keeps soaring.

Our plants merely blend and still require nitrogen, phosphate and potash components for fertiliser making, especially from the mentioned countries in conflict, but which are being procured costly for this reason and a heavy importation cost to worsened exchange rate gap.

But the immediate past government claimed it disbursed a ₦1trillion loan in its administration to assist rice farmers. 60% (or 75% according to the IMF) is yet to be paid back.

It was reported that a large majority of the beneficiaries of this facility wasn’t farmers hence the reason for the repayment default. However, even farmers that genuinely benefited from the scheme lamented a harsh economy in which they operated as reason for not being able to pay back.

The discussed rising production cost affects local competitiveness and is in part responsible for the declining hectares of rice production.

The cost of producing rice in Thailand, sending it down to Benin and entering Nigeria is lower than producing rice in Nigeria and dispersing for Nigerians.

Last year, ‘a 1,000kg of paddy needed to produce 12 bags of 50kg rice sold for $470 in Thailand compared to $607.5 in Nigeria’. With the CFA Franc stronger than Naira against the Dollar and Benin with a lower inflation rate than Nigeria, Thailand imported rice would reach Cotonou and cross into Nigeria at lower cost than Nigeria’s rice which would incur additional costs of energy, milling, packaging and transportation, all already impacted by inflation.

With an (unrestricted) open/porous border for dumping of foreign rice farmers are generally demotivated to continue production and rather start importing rice from neighboring countries or move to producing other crops.

This is worsened by farms being flooded, with grains washed off without farmers being adequately assisted or compensated and instead ravaging insecurity having the dogged, remaining farmers killed in numbers where the surviving ones are forced to abandon their farmlands and livelihoods, thus exacerbating supply gap.

The flooding in 2022 claimed ₦700 billion in farm investment. In 2020, 110 rice farmers in Borno were killed by insurgents and 78,000 farmers in the state and other significant food producing states in the north abandoned their farms in fear of terrorism. Economic loss to terrorism in the nation is estimated at $100billion.

Hence, with all these problems rice mills we spent billions to erect would experience paddy scarcity worst being in 2023 with many shutting down, but however supply had hovered around 8 million metric tonnes which could still guarantee 81% of our demand but wouldn’t with the unproductive postharvest factors still at play and paddy exportation to neighboring nations and Europe.

Yes we do export paddy, to Ghana, Botswana, Russia, France, Ireland, and Hungary.

It becomes apparent that the problem we face with rice -and as for other crops and agricultural commodities -is multifaceted and requires a multidimensional solution.

However, taking the decision to raise local rice production was necessary and a beneficial one today, because, how could we have survived/survive in a time of escalating supply chain disruption and rice price, where global rice price point rose by 30% between 2019 and 2023 to a level only seen in the 2008 financial crisis, with covid pandemic, Russia-Ukraine conflict, recurrent El Niño and La Niña weather effect, Red Sea blockage to Middle East conflict, and the world’s largest rice exporter India cutting its rice exports.

But raising supply alone and pursuing such expecting normalisation of rice price and availability without remedying other influencing factors is like pouring water down a basket expecting it to fill.

It is why I’ve always emphasised putting in charge people who understand the complexities and interconnectedness of these issues and can think different to engineer a sustainable solution.

India placed quota embargo and raised tariff to stem rice exports wanting to satisfy domestic demand with its rice supply impacted by irregular weather pattern. But we are exporting paddy rice when we can barely meet our paddy demands.

Countries choose their nations first. I’m not saying we should ban exporting; in fact, exporting can be a good means of generating foreign earnings (that could help remedy our forex crisis), but that we pursue such from a place of strength and with more focus on exporting value added products. Exportation goal can motivate us to build local capacity, rather.

We export raw cocoa beans, yam, cassava, etc earning little and associated benefits of employment and opportunities than importing nations, even when we are the key producers.

Whatever happened to exporting milled rice, packaged rice of different flavours, rice oil, flour, crisps, cereals, etc?

We can’t determine where farmers sell their produce to, and they will naturally retail to where’s more cost-effective and profitable.

There’s a reason why businesses would choose a stable market of a few buyers but higher purchasing power over a chaotic market of many buyers but low purchasing power.

There’s opportunity within as outside. We spend $1.3billion yearly importing rice. Imagine this money is trapped within.

The supply-demand gap should be seen as opportunity than a problem and should drive our action. Creating enabling business environment and invigorating the economy boosting purchasing power and lowering inflation would attract local producers to serve domestic market and foster economic activities –generating revenues and jobs.

Thus, issues as insecurity making investment landscape volatile must be honestly and thoroughly fixed eradicating the politics of it, because there can’t be food security without security -for (safety of) life, investment, which ensures peace and stability -for food production activities to take place.

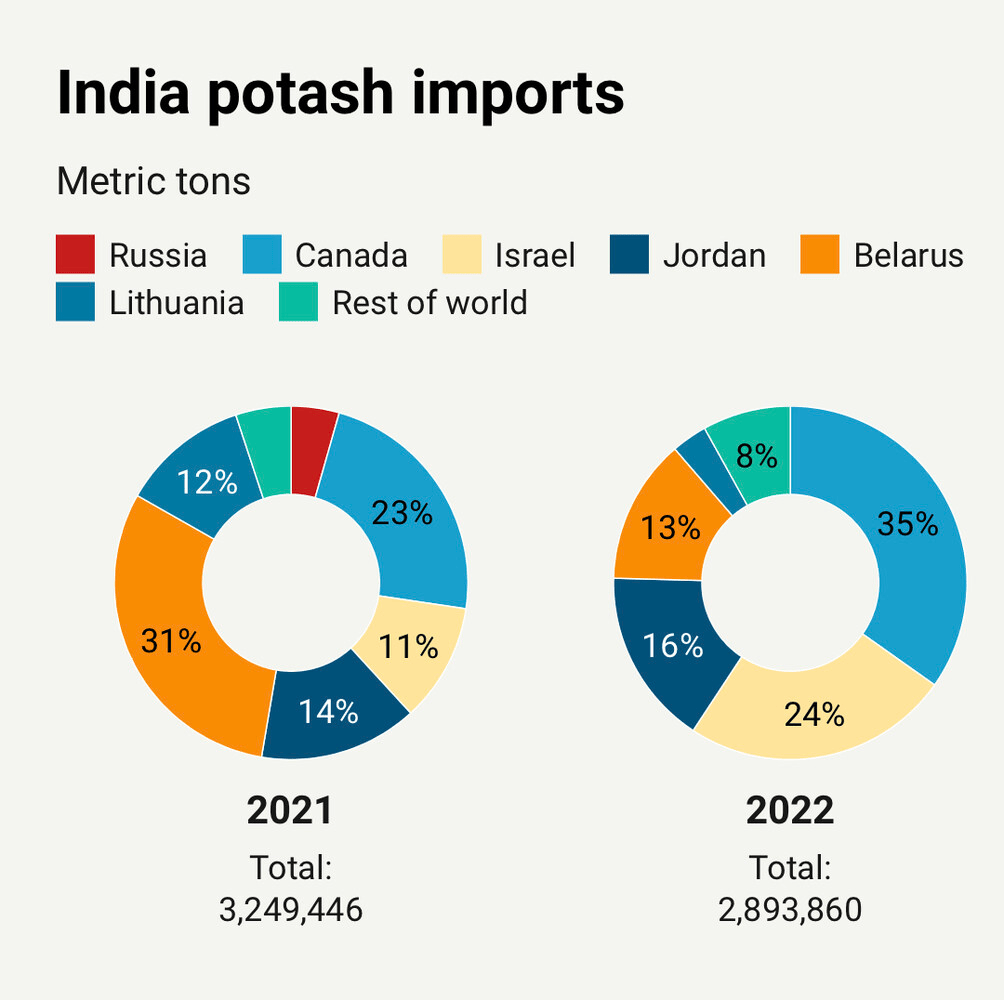

Also, fertiliser availability and accessibility can’t be a problem when we’ve got options and can think innovatively. When India’s fertiliser supply from Belarus and Russia was threatened with Russia-Ukraine conflict, the nation sought (more) alternative arrangement with other producing nations like Canada, Israel, and Jordan.

Nigeria can follow India and even establish procurement relationship with neighbouring African states having nitrogen, phosphate and potash deposits. Moreover, we have great stock of natural gas, organic matter remains, and rock deposits rich in these basic elements that can be used in making diverse fertiliser types. What is left is to chart a roadmap.

There is need for significant investment in extension system, its synergy with research bodies, and enabling participation of private bodies so as to raise extension workforce, develop hybrid inputs and ensure product of research reaches farmers. It does not tell well that there are prolific rice varieties but farmers suffer not being able to get hold of them.

Every year our tertiary institutions churn out thousands of extension graduates. We should utilise these people. This way we create employment for them.

Structure extension at local and state levels and equip these graduates to deliver extension service to farmers at community level.

Encourage farmer-to-farmer extension, farmer field school teaching, and simple (mobile) technology incorporation for extension service delivery.

This can help extend information on management of pests, weeds and diseases and adoption of good planting, harvest and postharvest practices for a productive production.

The state must institute stringent border checks and establish regional biosecurity relationship to keep at bay migratory pests and viral diseases, and also establish local forces and incorporate artificial intelligence to monitor pests and diseases population and work with research and extension in spreading awareness and in developing and disseminating preventive guidelines and solutions.

This relationship must also be exploited to mediate the control of dam opening from neigbouring nation, Cameroon that floods farms in Nigeria. Farms shouldn’t be flooded when we struggle to irrigate farms around the country.

How about developing protective measures knowing when flooding would happen based on accumulated data and updated weather investigations? How about also diverting for irrigation and storage for later use making use of existing channels and reservoirs and even fortifying or building new structures when not enough?

Our technical institutions shouldn’t go moribund as they are. Establish their linkage with local and foreign machine and parts manufacturers, research and extension bodies, to develop locally adaptive and effective machines for farming.

Make power stable exploiting diverse power generating sources, provide investment funds, and grant incentives and subsidies that make possible local manufacturing of and availability of affordable farm machineries. We can begin having machines run on alternative energy like solar powered irrigation which can help solve our irrigation problems. This can create a market that feeds other industries and opportunities for agricultural engineers.

Of important mention, is the need to provide more and robust funding, subsidies to the farmers to help them cushion rising production cost.

Agriculture cannot be left unaided and unprotected if we are to feed our nation. Moreover, climes seeing great progress with their agriculture give their farmers heavy subsidies and protections.

However, as we have seen with woes of rice farmers, we must understand that funding, subsidies, etc are not enough and won’t yield if we don’t put in place/promote enabling environment for the appropriate utilisation of these instruments.

Then we must ensure such assistance to go the right beneficiaries which entails knowing and having proper records of the targets. We must set the economy right, cut unnecessary expenditures, make business environment conducive and massive infrastructural investments.

It’s evident the global economy is in distress and nations are feeling the impact. But if we can put our affairs in order at home then we can cushion the effect, however, it would entail properly understanding the issues we face, building a robust action plan, being committed, dedicated and unyielding, taking bold risks and sacrifices, thinking different. And of all, having patience.